How I Slashed My Mortgage Stress with Smart Tax Moves

What if your mortgage could work *for* you, not against you? I used to dread tax season, staring at my home loan like it was a money pit. But after digging into overlooked tax strategies, everything changed. I discovered how smarter planning didn’t just lower my bill—it reshaped my entire mortgage journey. No jargon, no hype—just real moves that saved me serious cash. If you're paying a mortgage, this isn’t just about taxes. It’s about keeping more of your hard-earned money. Let’s break it down.

The Hidden Link Between Mortgages and Taxes

Most homeowners think of their mortgage as a fixed monthly expense—something to budget for, not something to optimize. But beneath the surface, there's a powerful financial relationship between your home loan and your tax return. This connection, often overlooked, can mean the difference between thousands in unnecessary payments and meaningful long-term savings. The U.S. tax code allows certain mortgage-related expenses to be deducted, effectively lowering your taxable income. When used wisely, these deductions transform a portion of your mortgage from a liability into a strategic financial tool.

At the heart of this advantage is the mortgage interest deduction. If you itemize your deductions, you can deduct the interest paid on up to $750,000 of mortgage debt for loans taken after December 15, 2017, or up to $1 million for older loans. This rule applies to both primary homes and second homes, making it one of the most valuable benefits available to homeowners. For someone with a $400,000 loan at 6%, that’s roughly $24,000 in annual interest—nearly $6,000 in potential tax savings for someone in the 25% tax bracket. Yet, many fail to maximize this benefit because they don’t understand how it works or assume they don’t qualify.

Another often-missed deduction is for property taxes. When paid through an escrow account, these are included in your Form 1098 and can be itemized alongside mortgage interest. In high-tax states like New Jersey or Illinois, annual property taxes can exceed $10,000, pushing combined deductions well above the standard deduction for many filers. But eligibility isn’t automatic. You must itemize, and the total must exceed the standard deduction amount for your filing status. For married couples filing jointly in 2024, that threshold is $29,200. If your mortgage interest and property taxes add up to $26,000, you’re leaving money on the table by not adjusting your strategy.

The real power emerges when you view your mortgage not as a standalone bill but as part of a broader financial ecosystem. Two homeowners with identical loans can have vastly different tax outcomes based on timing, loan structure, and financial decisions. Consider Sarah and James, both with $350,000 mortgages at 5.5%. Sarah makes her payments on schedule and doesn’t think about tax implications. James, however, prepay his December mortgage in November, accelerating his interest and property tax payments into the current year. That small shift allows him to exceed the itemization threshold, unlocking a $4,000 tax benefit. The loan is the same—but the financial result is not.

Timing Your Payments for Maximum Benefit

When you make mortgage and property tax payments can significantly influence your tax outcome. Most people pay on autopilot, never considering that shifting a single payment by a few weeks could trigger thousands in savings. The U.S. tax system operates on a calendar-year basis, meaning deductions must be paid within the tax year to count. This creates opportunities for strategic timing—especially for those who hover near the itemization threshold.

One effective technique is prepaying your January mortgage payment in December. Since mortgage interest is paid in arrears, the December payment covers November’s interest. But the principal portion of the January payment—and the interest for December—can be paid early. By doing so, you effectively add another month of mortgage interest and potentially another installment of property tax to your current year’s deductions. For someone paying $2,000 per month with $1,400 in interest, this move adds $1,400 to deductible interest. If this pushes you over the standard deduction, the tax savings could far exceed the cost of the early payment.

Property tax timing offers even greater flexibility. In many counties, homeowners can choose when to pay annual or semi-annual property taxes. If you expect a higher income this year or know you’ll be itemizing, paying your full annual property tax bill before December 31 ensures the entire amount counts toward this year’s deduction. Conversely, if you’re below the itemization threshold and expect higher deductions next year—perhaps due to a planned renovation or medical expense—delaying the payment until January may be smarter. This kind of control is rare in personal finance, yet it’s underutilized by most households.

Another scenario involves the alternative minimum tax (AMT). While fewer taxpayers are subject to AMT today due to recent tax reforms, those who are may find that timing deductions doesn’t always help. However, for the vast majority not subject to AMT, clustering deductions in high-income years can be a powerful strategy. Imagine a homeowner who receives a large bonus in December. By accelerating mortgage and property tax payments, they increase deductions in a year when their marginal tax rate is higher, thus saving more per dollar deducted. The same deduction taken in a lower-income year would yield less benefit. This is the essence of tax efficiency—aligning financial actions with tax circumstances.

Real-world results speak for themselves. Lisa, a school administrator in Ohio, used to pay her semi-annual property tax in June and December. After consulting a tax advisor, she shifted both payments to December, consolidating them into one tax year. Combined with her mortgage interest, this pushed her total itemized deductions from $24,000 to $31,000—above the standard deduction. The result? An additional $1,800 in her tax refund, simply by changing when she wrote the check. No extra spending, no financial risk—just smarter timing.

Itemizing vs. Standard Deduction: The Real Math

For homeowners, the choice between itemizing deductions and taking the standard deduction is one of the most consequential financial decisions each tax season. The standard deduction is simple and automatic: $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for married couples filing jointly in 2024. But itemizing allows you to deduct specific expenses, including mortgage interest, property taxes, and charitable contributions—if they exceed the standard amount. The challenge lies in calculating whether your deductions cross that threshold.

Mortgage interest is typically the largest component. On a $300,000 loan at 6%, annual interest in the early years can exceed $17,000. Add property taxes—say, $6,000—and you’re already at $23,000. For a single filer, this is below the standard deduction, so itemizing offers no benefit. But for a married couple, $23,000 still falls short of $29,200. It’s only when additional deductions like charitable gifts, medical expenses, or state taxes are included that itemizing becomes viable. This is why many middle-income homeowners don’t benefit from the mortgage interest deduction—they simply don’t have enough total deductions to justify itemizing.

Regional differences play a major role. In high-property-tax areas like Westchester County, New York, or Cook County, Illinois, annual taxes can exceed $15,000. Combined with mortgage interest, that can easily surpass $35,000—making itemizing a no-brainer. But in states with low property taxes, like Alabama or Wyoming, the math may not add up. Homeowners in these areas must rely more on other deductions or accept the standard deduction as their best option.

Decision-making tools can clarify the choice. Most tax software programs automatically compare itemized and standard deductions, showing which yields a lower tax bill. Some even simulate the impact of prepaying expenses or making charitable gifts to “bunch” deductions into a single year. This strategy, known as “deduction clustering,” allows taxpayers to alternate between itemizing and taking the standard deduction, maximizing benefits over time. For example, instead of donating $5,000 annually, a homeowner might donate $10,000 every other year, combining it with accelerated mortgage and property tax payments to exceed the threshold in alternating years.

The break-even point varies, but a general rule is that total itemized deductions must exceed the standard deduction by at least $1,000 to make the extra effort worthwhile. Time spent gathering forms, reviewing statements, and completing extra tax forms should be justified by real savings. For many, the convenience of the standard deduction outweighs the marginal benefit of itemizing. But for those with larger mortgages, high property taxes, or significant charitable activity, the rewards of itemizing can be substantial—and recurring.

Mortgage Refinancing with Tax Strategy in Mind

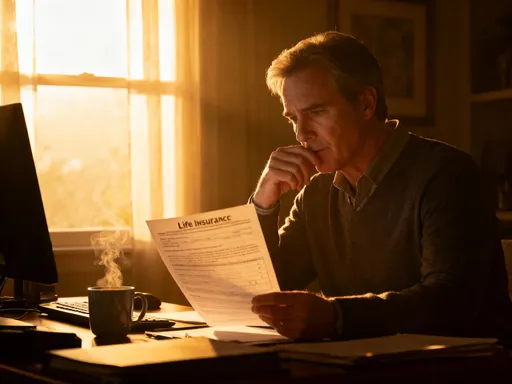

Refinancing is often pursued for a lower interest rate or reduced monthly payment, but its tax implications are rarely considered. Yet, refinancing presents a unique opportunity to align your mortgage with long-term tax efficiency. When done strategically, it can preserve or even enhance your ability to claim valuable deductions. The key lies in understanding how refinancing affects mortgage interest, loan points, and the treatment of closing costs.

Loan points—fees paid to lower your interest rate—are generally tax-deductible, but not all at once. If you refinance, points must be amortized over the life of the new loan. For example, if you pay $6,000 in points on a 30-year mortgage, you can deduct $200 per year. This spreads the benefit but ensures long-term value. However, if you refinance again in five years, any undeducted points can be written off in full in the year the loan is paid off. This creates a tax incentive to refinance thoughtfully, not impulsively.

Cash-out refinancing requires special caution. While it can provide funds for home improvements or debt consolidation, only the interest on up to $750,000 of acquisition debt is deductible. If you refinance a $400,000 mortgage and take out an additional $100,000 for a vacation, the interest on that $100,000 is treated as personal loan interest—non-deductible. However, if the same $100,000 is used to add a new roof or renovate the kitchen, the interest may remain deductible, provided the total mortgage doesn’t exceed the limit. The IRS requires documentation proving qualified use, so receipts and contracts must be kept.

Timing the refinance with life events can also enhance tax outcomes. Someone nearing retirement may refinance to a 15-year loan, increasing payments but shortening the loan term. While annual interest decreases over time, the higher early payments mean more deductible interest in years when income—and tax rates—may still be high. Conversely, refinancing during a low-income year may reduce the value of deductions, since each dollar saved is worth less at a lower tax rate. Coordinating refinancing with broader financial transitions ensures that tax benefits are maximized when they matter most.

Consider Mark and Elena, who refinanced their $380,000 mortgage from 6.5% to 4.5% just before Mark’s sabbatical. By locking in a lower rate and adjusting their payment schedule, they reduced monthly outflows while preserving the ability to itemize. They also used part of the savings to prepay property taxes, further boosting deductions in a year with irregular income. Their tax advisor confirmed the move would save them over $2,500 annually in after-tax costs—not just from lower rates, but from smarter tax positioning.

Leveraging Home Equity the Tax-Smart Way

Home equity is a powerful financial resource, but tapping it without considering tax rules can erode benefits. Home equity loans and home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) offer flexibility, but their interest deductibility depends on how the funds are used. Under current tax law, interest on home equity debt is deductible only if the loan is used to buy, build, or substantially improve the home that secures the loan. This means using a HELOC for a kitchen remodel qualifies; using it for a car or credit card payoff does not.

The $750,000 mortgage debt limit applies to the combined balance of all home loans. If you have a $500,000 first mortgage and take out a $100,000 HELOC for renovations, the total $600,000 falls within the limit, and the interest on both loans may be deductible. But if you take out the same HELOC for a vacation, the interest loses its tax advantage. The IRS does not require lenders to track usage, but taxpayers must maintain records proving qualified purpose. Without receipts, invoices, or improvement contracts, a deduction could be disallowed during an audit.

Some homeowners mistakenly believe all home-related debt is automatically deductible. This misconception leads to costly errors. For example, using a HELOC to pay for college tuition may ease cash flow, but the interest is not deductible as student loan interest unless the loan meets specific criteria. Similarly, using home equity to start a business may offer other tax benefits, but mortgage interest deductions do not apply. The key is intention and documentation: the loan must be tied to the home, and proof must exist.

Strategic use of home equity can yield dual benefits—home value appreciation and tax efficiency. A $50,000 renovation might cost $5,000 annually over ten years, but if it increases home value by $75,000, the return is substantial. Add to that the potential tax deduction on the interest, and the effective cost decreases. Over time, this approach builds wealth while reducing tax liability—a rare win-win in personal finance.

Avoiding Costly Mistakes During Tax Filing

Even well-intentioned homeowners can lose thousands due to simple filing errors. The most common mistake is misreading Form 1098, which reports mortgage interest paid during the year. Many assume the amount in Box 1 is fully deductible, but it includes only interest—not escrow payments for property taxes or insurance. Taxpayers must review their annual escrow statement to determine how much property tax was actually paid and report that separately on Schedule A. Confusing escrow contributions with deductible payments leads to overstated deductions and potential audit risk.

Another frequent error is failing to report the correct taxpayer name or loan address, especially after refinancing or moving. Discrepancies between your tax return and the lender’s records can trigger IRS notices, delaying refunds and requiring additional documentation. Similarly, if you refinanced mid-year, you may receive two Form 1098s—one from the original lender and one from the new. Both must be reported to capture all deductible interest.

First-time homebuyers may miss out on state-level credits or incentives. While the federal first-time homebuyer credit has expired, many states offer tax credits, down payment assistance, or property tax freezes for qualifying purchasers. These benefits require separate applications and are not automatically granted. Homeowners who don’t research local programs may overlook thousands in savings.

Record-keeping is essential. The IRS recommends keeping tax records for at least three years, but for homeowners, longer retention is wise. Loan documents, settlement statements (HUD-1 or Closing Disclosure), improvement receipts, and annual escrow summaries should be stored securely. Digital copies are acceptable, but they must be complete and legible. A well-organized file can prevent stress during audits and support future tax decisions, such as calculating capital gains when selling.

One taxpayer in Michigan filed without realizing his lender had reclassified part of his mortgage payment as loan assumption fees, reducing the reported interest. He deducted the full amount based on his bank statement, not the Form 1098. The discrepancy led to a notice, a recalculated tax bill, and a $420 penalty. A simple review of the form could have prevented the error. These cases underscore the importance of accuracy over convenience.

Building a Long-Term Tax-Aware Mortgage Plan

True financial resilience comes not from one-time moves, but from consistent, integrated planning. A tax-aware mortgage strategy evolves across life stages, adapting to changes in income, family size, and financial goals. In the early years of homeownership, maximizing deductions through itemization and timing can free up cash flow. As equity builds, strategic use of home loans for improvements can enhance both living standards and tax efficiency. And in later stages, preparing for home sale or downsizing requires understanding how past decisions affect capital gains and future tax liability.

This approach requires coordination with broader financial planning. Retirement accounts, investment income, and pension withdrawals all influence tax brackets and deduction value. A mortgage that made sense in a 25% tax bracket may need reevaluation in a 12% bracket. Working with a tax professional annually ensures that mortgage decisions align with the bigger picture. It’s not about chasing loopholes—it’s about making informed choices that compound over decades.

Technology also plays a role. Personal finance software can track mortgage interest, property taxes, and net worth over time. Some platforms integrate with tax programs, automatically importing data to simplify filing. Alerts for year-end payment opportunities or refinance breaks can prompt timely action. These tools don’t replace judgment, but they enhance awareness and precision.

The goal is not to eliminate taxes, but to pay no more than necessary. Every dollar saved through smart mortgage tax planning is a dollar that stays in your pocket—available for emergencies, education, retirement, or peace of mind. Homeownership is already a major financial commitment. By aligning it with intelligent tax strategy, it becomes not just a place to live, but a cornerstone of lasting financial well-being.